Inhabiting new space is often a matter of trial and error. New spaces can often be confusing or frustrating for inhabitants until they ‘see’ how they might use them. Bridging design and use requires an alignment between organisational ethos, inhabitant practices, and the spaces themselves. Fiona Young discusses how a ‘user guide’ might help inhabitants transition to new spaces, and in their ongoing use.

When we buy a new appliance it’s likely to come with instructions on how to use it. But when users encounter new buildings or spaces, they tend to be left to their own devices to uncover available features or to troubleshoot potential issues that might arise.

For example, we’ve all probably experienced coming up against a bank of wall switches and spent more time than we’d like trying to work out how to turn on the one we need. Or what about mixed mode ventilation systems where the air conditioning is permanently left on, as users don’t realise that they need to take control to activate more natural modes when external conditions are suitable?

Even if users are told how to use building features, how can we be sure that this knowledge is passed on to all users? At one K-12 school which had a new library with a mixed mode ventilation system, natural ventilation was never enabled. Upon further enquiry, it was found that only the school’s primary students learnt about this feature from a presentation given to their year group by the architect. However, staff who have more agency in activating building controls hadn’t been given the same information and weren’t aware of the need to manually override the AC to optimise the benefits of the mixed mode system.

Perhaps buildings too need a user manual for their inhabitants?

How can we more seamlessly bridge between design intent and occupation for better outcomes? One option is to integrate clearer signals into building design so that building features and intentions are more obvious to users. However, often a less-is-more aesthetic in architecture may be incompatible with additional signage or instructions applied to building surfaces.

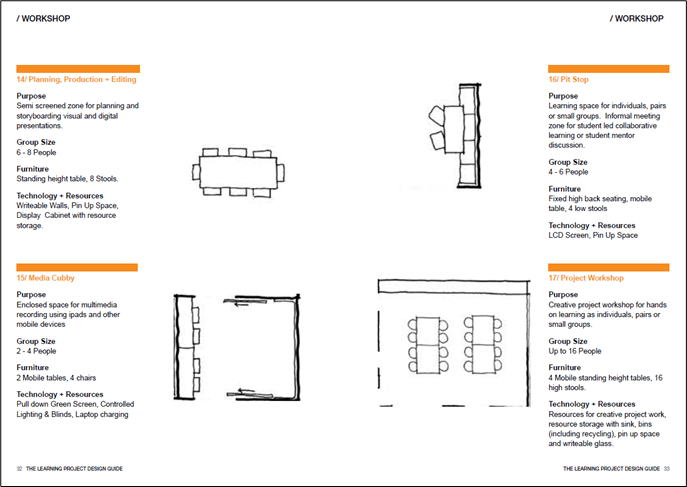

A few examples of User Guides have emerged in the education sector to support schools and their staff in using new types of learning environments. Caulfield Grammar’s Design Guide captures a graphic catalogue of the different space types within their “Learning Project” building, a prefabricated modular prototype learning space. Each space is shown outlining its purpose, size, furniture, technology & resources to help staff understand the features offered by each space.

The Learning Project Design Guide, Caulfield Grammar. Image courtesy of Hayball.

Providing further insight from a user perspective, Wesley College in Perth, Australia, developed an Agile Spaces User Manual to facilitate use of their new integrated science building. This document provides context for why the new spaces were designed, defined vocabulary around the various spatial typologies available, and included guidance for how teachers might plan to use shared spaces together.

Obviously, using a building is much more complex than using a toaster. There are many layers to a building from the Shell and Services (constructed form) to Scenery and Settings (the space within and without). And there are likely to be many more users inhabiting a building in a range of different ways at different times of the day.

So what should a User Guide for a building look like? On one level, it may be useful for people to be able to see diagrams of features or spaces and learn about the intention behind their design. At another, it is equally, if not more important for them to understand protocols or have shared expectations that will empower them to effectively use and share environments together.

As spaces and their uses evolve over time, how might a User Guide enable user reflection and incorporate change? What format should it take? Who should be involved in creating it? And how best do we capture the inputs of those involved? If you have an example of a process of creating a building user guide that supports the bridging of design and use over space and time, we would love to hear about it.

Fiona Young is an architect and researcher at Hayball Architects in Sydney, Australia. She is also one of the co-authors of Integrative Briefing for Better Design.