MADE by the Opera House, also known as the Multidisciplinary Australian Danish Exchange, is an Australian-Danish exchange program that is offered to Australian and Danish students of architecture, engineering and design (in the built environment). Between 2014-2023, each year five students from a NSW university and five students from a Danish tertiary institution participated in the program in Denmark and Australia respectively. This year, for the first time, a student from the field of Strategic Design was part of the program. Isac Lindberg reflects on the MADE experience as a collaboration across disciplines and on the role of strategic thinking to get to the heart of the problem to be solved.

In late August, I found myself presenting in the Utzon Room at the Sydney Opera House. As part of the Sydney Opera House MADE program, I had just completed a six-week interdisciplinary exchange where I collaborated with four other students from different Danish universities who specialised in architecture, engineering, and design. Despite the obstacles of working as a group of initially, complete strangers, this experience highlighted the significance of interdisciplinary collaboration and how our diverse skills and ideas played a vital role in shaping our proposal for the Opera House’s Central Passage.

I was unsure how my role as a Strategic Designer would fit into a team of architects and engineers. I didn’t know much about architectural masterpieces like the Opera House, and I was unaware of Utzon’s legacy. Initially, I perceived the building as having a prestigious, exclusive reputation. However, our brief was to create a proposal for the Central Passage to align it with the Opera House’s vision of becoming “Everyone’s House.”

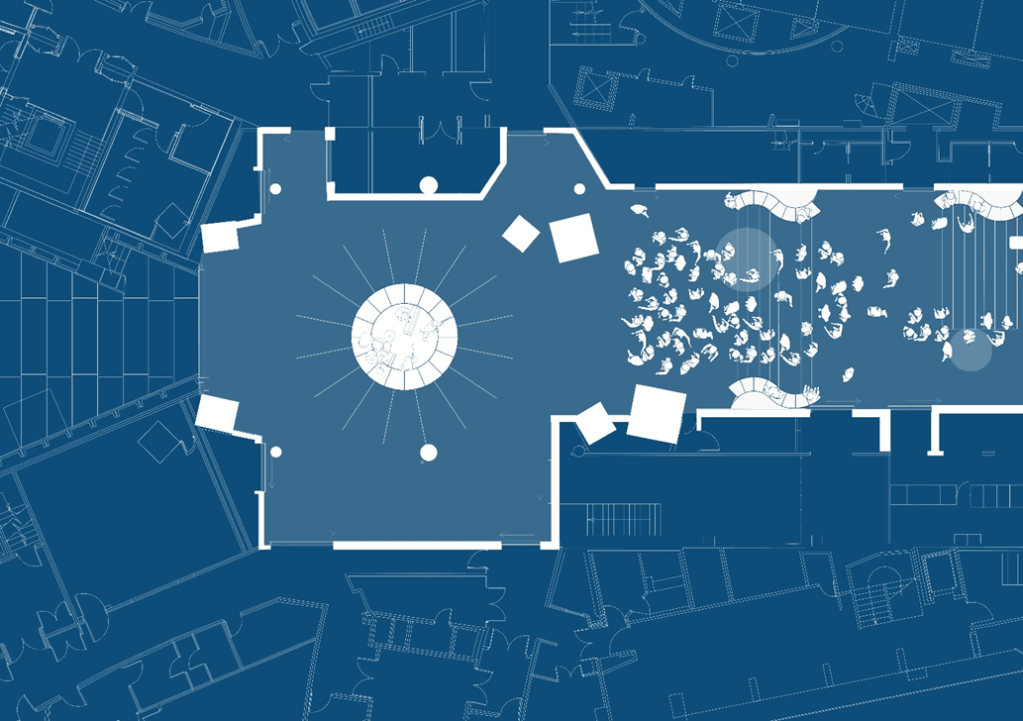

Currently, the Central Passage serves as temporary storage space and an access route for staff. It is situated between the iconic sails of the Sydney Opera House, with two main openings – one in the south and another towards the “Northern Broadwalk”. While the brief was inspiring, it also posed a significant challenge from the start: Who is ‘Everyone’? Who should be included? and Who should not? and How can we cater to everyone?

The Central Passage looking toward the Northern Broadwalk.

To tackle this challenge, we conducted mind-maps, workshops, and discussions to delve into the core of the problem. We met with local Aboriginal women who helped us understand how important the land which the building is built on is for Aboriginal Australians. This was something entirely different from what I had encountered before and had a profound impact not only on our project but also on the way I now approach my work.

As discussions progressed, it became clear that the concept of ‘everyone’ was challenging to translate into a workable solution. Ironically, our attempt to design for everyone risked weakening our focus and creating something that failed to resonate with anyone. It wasn’t until we conducted on-site research that we fully grasped the needs and requirements of those who interact with the building. We gathered insights from internal stakeholders ranging from security, through to performers, office staff, visitors, and leaders in the built environment. This enabled us to define three distinct user groups:

- Frequent visitors: Those who work at the Opera House and/or who come to watch shows.

- One-time visitors: Those who are interested in the Opera House’s heritage and architecture.

- Infrequent visitors: Locals who rarely or never visit the Opera House.

Addressing this final category raised a crucial question – How could we make the Opera House appealing to locals who currently have no affiliation with the building while still accommodating frequent visitors? By narrowing our focus to a specific audience, we could, for the first time, tailor our design based on the needs and expectations of the users. Through this process, we arrived at a proposal that not only resonated with Jørn Utzon’s vision to open the Central Passage to the public, but also appealed to a new audience.

2023 Australian MADE program proposal: Rethinking the Central Passage as “The Meeting Point” between visitors and performers, the indoor and outdoor, two heritages, and of MADE projects.

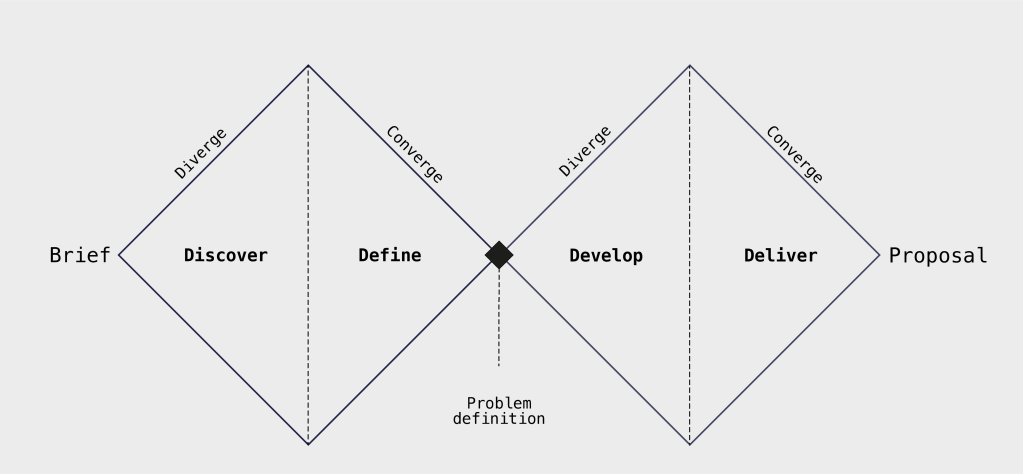

What I found interesting was that we all had different ways of working. Some were more comfortable when concrete progress was made, while others were more accustomed to the uncertainty of the early stages of the process. This was something I learned to appreciate from my time at the Royal Danish Academy, especially during the “Discover” phase of the Double Diamond Model. In this initial stage, we shape the context by distancing ourselves from assumptions and adopting the user’s perspective. This step is critical because, without context, our design decisions lose their meaning and purpose, leading to indecisiveness.

Looking back on my journey, I’ve realized how crucial it is for people with different skills to work together. I think diversity should be a key principle in design, especially when dealing with complex issues and various stakeholders. This involves fostering collaboration across various fields, strategic thinking, and most importantly, gaining a profound understanding of the users and the context of the problem we are trying to solve. From where I stand, it’s clear that making objective decisions rather than subjective ones is essential when we want to design for inclusivity and diversity.

2023 Australian MADE program students presenting their proposition with the Utzon tapestry behind them: (L-R) Astrid Bjørn Dønnem, Ditte Gyldendal Amby, Marie Jul Scharff, Christoffer Brødsgaard & Isac Lindberg.

Isac Lindberg is a Helsinki native, currently studying Strategic Design at the Royal Danish Academy. With a background in Industrial Design, Isac enjoys the puzzle of trying to understand how people interact with spaces and objects, both physical and digital.

Pingback: Disrupting Practice: Findings from the Practice Innovation Lab | Integrative Briefing for Better Design